In our last post, you were a beetle with a breathing problem. In this one, you’re underwater.

This tiny insect, barely larger than a grain of rice, is a baby mayfly (a mayfly nymph). It spends the first years of its life entirely submerged, then crawls up into the air, and flies off. We couldn’t help wonder, how does it breathe down there?

If we opened our air passages (our nose and mouth) in a tub of water we wouldn’t last a minute. We’d drown. In some (less friendly) circles, this is called ‘waterboarding’, but you can’t waterboard a mayfly nymph. Dunked, it breathes easily. It’s solved this problem. But how?

The solution is looking right at you. If we move in a little closer, notice what looks like a set of feathery objects, protruding out on this animal’s left and right, down toward its butt…

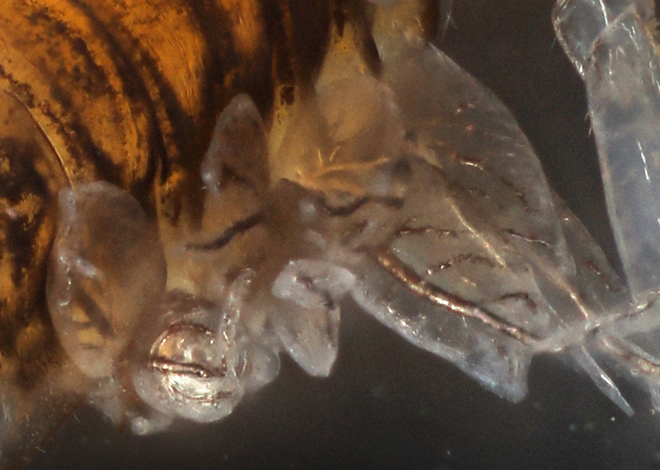

Move in closer still, and you’ll notice there are copper-colored branching tubes inside each of those feathery folds. They look like veins in a leaf. Those are its breathing tubes.

You can see them clearly here.

We keep our breathing parts inside us (our mouth, nose, windpipe, lungs). So do all land animals, including insects. But underwater breathers don’t. They stick their breathing tubes out into the water. That’s what those feathery objects are; they’re gills. Mayfly nymphs extend their respiratory system out into the surrounding water, effectively rearranging their insides to be closer to their outsides.

And they breathe this way for a very compelling reason: oxygen in water is harder to find. 21 percent of the air is oxygen. In water? Oxygen is less than 1 percent.

Yup, that little.

So animals in the water don’t dare wait around for oxygen to come to them. They have to find ways to get out and meet more oxygen molecules. Sticking body parts further out is a help. That’s all gills are, a way for a creature to get its air-breathing insides closer to any passing oxygen.

Another Problem: Oxygen’s Stuck

But even with gills, there’s another big problem that underwater breathers have to solve – what little oxygen there is in water, barely moves.

In our last post, we took a clump of air, and found that oxygen (that red dot) is so hemmed in by other molecules, it gets kind of stuck, like a heavy metal fan in a mosh-pit. In air, an oxygen molecule bumps into its neighbors 6 billion times every second (that’s a pretty epic mosh-pit).

That’s air.

In water, an oxygen molecule is even more hemmed in, an astonishing TEN THOUSAND TIMES MORE. It has 60 trillion collisions every second, random zigs, zags, sometimes up, sometimes down, sometimes left, sometimes right. It’s so stuck in place, it barely gets anywhere.

Move or Die

Which is why gill-breathing creatures have no choice. They’ve got to keep moving, or figure out a way to stroke the water, to draw in a fresh supply of oxygen. Because consider what happens if you’re a gill breather and you find yourself in still water. Let’s say you decide to hang out for a while in the same spot.

Oh dear.

Because oxygen molecules in water are basically stuck in place, you can actually use up your local supply and die. That’s why fish keep gulping water – to keep a steady stream of oxygen rich water flowing past their gills.

So when in still water, gill breathers need to ensure there’s a flow. Most do this by constantly moving around, leaving a trail of oxygen depleted water behind them, like goats mowing through a field of grass.

Some insects take a more laid back approach to breathing. Mayfly nymphs, who we met earlier, don’t need to chase after oxygen molecules. Instead, they stay in place and fan their feather-like gills to and fro, creating little currents of water that bring in a fresh oxygen supply.

But there’s one amazing insect that rises to the challenge of finding a fresh oxygen supply in a rather unusual way. Instead of moving itself through the water, it moves the water through itself.

The dragonfly nymph has its gills inside its rectum, and it breathes through its butt-hole. Yup, you read that right. In ‘inhales’ by sucking water into its butt, and ‘exhales’ by squeezing the water back out.

“Whaaaat?“, said Robert on first hearing this.

Robert: …this is true?

Aatish: I’m not making this up.

Robert: But we just said gills are for sticking OUT, now you’re saying these stay IN?

Aatish: Whatever works, I suppose.

Robert: But how would this work? You say the gills are up this animal’s butt?

Aatish: I did.

Robert: The same butt it poops out of?

Aatish: The same.

Robert: Well, how do I say this delicately. Wouldn’t it be a little… what’s the word?… unhygienic to breathe and poop through the same orifice?

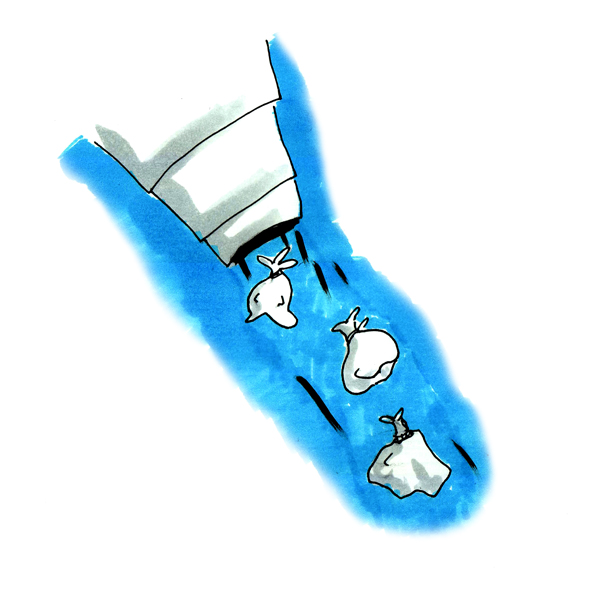

Aatish: It would, which is why dragonfly nymphs have evolved their own biodegradable garbage bags – a thin membrane that wraps around their poop to keep it from polluting its surroundings.

Robert: Come on.

Aatish: No, really, these creatures swim around with their own built-in waste disposal system.

Robert: Have you seen these packets?

Aatish: I haven’t, but I’ve read about them. They’re called peritrophic membranes, and lots of insects use these poop baggies to clean up after themselves.

Robert: Well, I’m going to try to imagine them…

Aatish: Don’t…

Robert: …is this what you imagine?

Aatish: I was trying NOT to imagine them.

Robert: Oh.

Having gills inside (rather than outside) the body gives the dragonfly nymph a few terrific advantages. Not only does it attract fresh oxygen, there’s a totally neat side-effect – jet propulsion!

By squeezing water out of its butt, the dragonfly nymph can propel itself in the opposite direction, rocketing itself safely out of harm’s way, or launching it towards its lunch (hooray for Newton’s third law). As far as we know, dragonfly nymphs are unique among insects in this ability.

But the thing that makes this little baby dragonfly even more spectacular is what those rocket blasters appear to do for its self confidence.

As you’re about to see, it uses its rocket blasters not only to move about the pond, but the same water squeezing system powers a grasping arm on its face – it’s a terrifying stretchable mouth part, that flings outward and takes food into a death grip.

In this video you will watch it effortlessly consume 6 little insects in a row, most of them baby mosquitos (good riddance!) but then it gets all cocky and goes after an impossibly large passerby – which makes no sense. It would be like one of us trying to bite a cow, and yet, if you’ve got rockets in your butt, apparently you become an optimist.

https://youtu.be/r-k-iG9d1go?t=1m41s

We should end here.

You can’t top a dragonfly nymph’s breathing system – or can you? We can’t help ourselves. We’ve decided to add one more addendum to our addendum. “Noticing” does this to us. So, if you come back in a little bit, we promise you three little breathers who get their oxygen in surprisingly unexpected ways, by breaking through, breaking in, or hanging on. They’re guaranteed to… [Aatish: Don’t do it, Robert. Don’t go there.] take your breath away. [Aatish: Noooo!]

Footnotes

We first heard about bewildering butt-breathers and other curious aquatic insects from Professor Gilbert Waldbauer, who describes these delightful characters in A Walk Around the Pond. Waldbauer is an entomologist and a keen noticer, and his book is an eye-opening look into the surprisingly varied and interesting world of tiny critters.

And big thanks to expert insect photographer Jan Hamrsky, who gave us permission to use his images of dragonfly nymphs. Lose yourself in his stunningly beautiful collection of insect photographs on his website Life in Fresh Water.

Also, thanks to Cynthia Berger, for sharing some astonishing dragonfly facts with us. Her book on dragonflies is a delight.